June 13th, 2010

Janis Joplin performing in San Jose in 1968. (Photo by Jim Marshall)

History changes with time. Views of the past are said to be products of the era in which they are examined, and  I think this is also true on a much smaller scale: how we, as individuals, understand the world at any given moment.

From time to time, I will revisit something—a recording, an artist, a piece of literature—to see if I still dislike it. Occasionally I change my mind. Why? Just as our understanding of historical events changes because of where we sit, so, too, does our take on specific examples of culture because of the time in which we live or the experiences we’ve accumulated over the years.

Last night I decided to do the opposite of my usual exercise—rather than wanting to check on whether something was as “bad,†as I remembered it, I wanted to verify that I was holding onto a memory that still resonated with who I am now. When I was in 9th grade, Janis Joplin returned to Austin, Texas after a long absence to give a concert. My remembered experience places the performance among the best I’ve ever seen. That is saying a lot—I see live music as often as I can, though it feels more and more like “I’ve heard that already.â€

A music blog I was reading recently included a link to two clips of Joplin performing during the last years of her life on the Dick Cavett show. She goes from being interviewed (about 2 minutes in) to a stage with her band and inhabiting the songs in a way that most musicians can only dream of. Her official recordings—mostly done in a studio—do not reflect the amazing transformation that took place on those television studio stages. As I had only these albums as touchstones, I began to doubt the validity of my experience. I am happy to report that the videos I saw eliminated any doubt about my memory of the concert I attended.

It occurs to me I was also confirming something about myself. We accumulate a wealth of core experiences throughout our lifetime, and these things contribute to defining who we are. There was something about the honesty and directness of Joplin’s performance that made me realize how important it is to remember what is possible in a world defined by the status-quo. It takes courage and commitment to get to magic. Maybe we should reprise the slogan “Be Here Now.â€

Excuse me, I have to sign off now. I’ve got to watch that video again.

NOTE:

Check out the book Trust: The Photographs of Jim Marshall.

Tags: art, commitment, Janis Joplin, Memory, music, performance, presence

Posted in Uncategorized | 1 Comment »

June 5th, 2010

Too often we dismiss white space in art and print and silence in music as nothing. The reality is that it is very much something—as much a part of what we understand about the art we encounter as what we might call the substantive part. In fact, the absence of these “nothings†would propose very different readings of pieces before us.

In Josef Alber’s famous book, Interaction of Color, he talks about how colors do not exist in a vacuum. Individual colors are understood in context; that is, what surrounds a color is an important part of how we perceive it.

The same is true in music. Morton Feldman composed many pieces that forced his listeners to consider notes differently than usual because of the space with which he surrounded them. Remove them, and they become entirely different pieces.

Of course, the most famous piece about silence, 4’33” by John Cage, is not really about silence at all. It is about listening.

Besides the reverb which bathes each recording on the German label ECM, every one of their CDs start with 4 or 5 seconds of silence. In this way, the first sounds of the performance are heard differently than if they began instantaneously. That approach has another effect: it separates the music you are about to hear from the world of ordinary sounds. (Think of what we consider to be ordinary sounds these days as compared to 100 years ago!) It is the label’s way of setting the experience apart from normal life, should you choose to really listen. Not unlike what is attempted during the services in sacred buildings.

A print or drawing with a mat around it in a frame is saying the same thing: this is special—pay attention, and you’ll be rewarded. The “white space†of the mat helps to ensure that other elements in the area in which the art is displayed do not become part of the viewer’s experience.

Often I have clients tell me that I have an excellent opportunity to add more information to an ad or brochure because of the white space I have employed—usually used deliberately to make the piece more effective. The irony is that less will be communicated because it would have become more difficult for a viewer to enter and engage with the material. (In many cases, it is a question of the client not having gone through the exercise of deciding what are the most important messages to be delivered and wanting to cover all their bases: a case of too much is not enough.)

I’ve talked about the effect that these “nothings†have on the “substantive†part of things, but what about looking at it the other way around? The spaces and silences are all bordered by their opposite, and so are limited by their borders. Sounds like shapes to me—again, that’s really something!

Long live nothing.

Tags: ads, advertising, computer design, Design, Interaction of Color, John Cage, Josef Albers, Morton Feldman, music, silence, sound, white space

Posted in Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

June 2nd, 2010

Tags: Concord MA, flood, signs, water

Posted in Uncategorized | Comments Closed

May 26th, 2010

I am amazed that in 2010 I am still encountering foot marks masquerading as apostrophes in printed materials. Considering the cost of an ad in The New York Times, you’d think they’d get it right. This ignorance is surely a legacy from when the PC eliminated the informed work of seasoned typographers.

And what amazing work they did. You would “spec†up a page of text to fit into a brochure or ad, confident that you were in good hands. Copy that shouldn’t have really fit in the space you had assigned it, not only lived comfortably there but was beautiful, too.

However, once the ubiquitous computer became the typography engine of our layouts, we were expected to take over. Many designers took up the challenge, using their Macs to work up ideas that previously had been difficult or impossible to realize.

There was a year during which we were all informed that since there was a layout program called Pagemaker available, our services were no longer required. Administrative assistants were enlisted to create brochures and logos, throwing into question everything we knew or were taught about marketing materials communicating something intrinsic about the company that issued them. Eventually, designers were brought back to the table, but the damage was done. The availability of all kinds of software now meant that companies would see their computers less as tools than employees. (I think we could probably call its current visual manifestation “the PowerPoint aesthetic.â€)

There’s another ingredient at work here—and one not necessarily negative. With today’s availability of inexpensive and sophisticated electronics, the 70s do-it-yourself approach continues to live on. The DIY means-to-an end often embodies a challenge to a prevailing set of rules, resulting in some odd combinations—often strange, but usually interesting. Their challenges to traditional typography sometimes even take the form of radical transformation of letterforms. That is not say that some pretty stupid decisions aren’t made under the DIY banner.

So what is this rant all about? Â Intention. That is what design and communication are all about.

Tags: ads, computer design, DIY, intention, layouts, typography

Posted in Uncategorized | 2 Comments »

May 24th, 2010

Unfortunately, as we acquire more and more recordings online as audio files, we are losing valuable information that can really add to our understanding of the music. Just as we think of milk as coming from the supermarket instead of the cow, now music is “made†by the web. I remember spending hours in record stores when I was young, looking at the lp covers and reading all of the information on the jacket as a way to put the music into context. (Of course, it was also great excuse to hang around and hear what was being played in the store—that’s how I heard the first David Grisman Quintet album when it came out in 1977.)

The searching for context could sort of be put in two categories.

1. Information that the record company wanted me to know. This was not always the most interesting or helpful way to get an idea of the contents inside the record jacket! The cover often used graphic design as a way to engage the intended audience’s demographic, and the notes on the back often indulged in so much hyperbole that it was easy to dismiss them as the blathering of the in-house marketing department. Some covers did become such a strong expression of the label that the opposite occurred—you began to trust it when you saw it. (The design of covers from sixties Blue Note and Impulse releases are good expressions of that—great branding cases, both, too.)

2. Information gleamed from another type of reading. Where was the album recorded? Who played on it? Who produced it? What label was it on? What instruments were played? Answering those questions often led me to a better sense of what I might hear and gave me a way to continue exploring if I liked what I heard. Sometimes, the takeaway was related to the consistency of presentation—when I saw a poor design job I often wondered about the quality of the actual recording, since they didn’t seem to have taken much care with the part that I could actually see.

I am in mourning for record jackets, though I have come to terms with CD packaging, even if don’t have the impact of the old lp covers. The visual face-off between the Beatles and the Stones with Sgt. Pepper’s and Their Satanic Majesty’s Request would have seemed much less important than it did if first delivered in jewel boxes. (At least they are portable.)

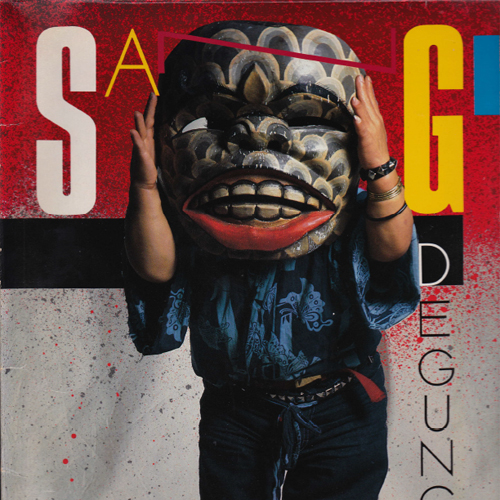

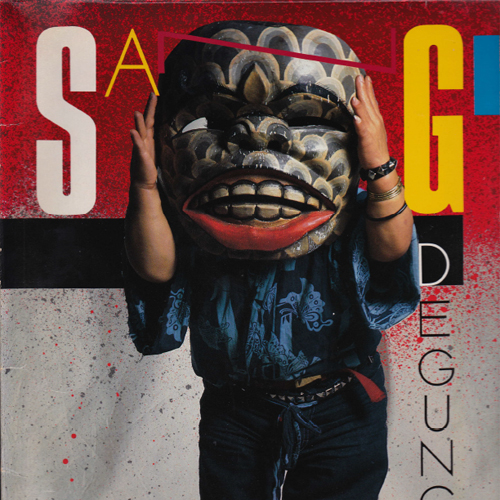

Perhaps the “packaging†for digital audio files is the Wikipedia entry, the MySpace page, and YouTube videos. If so, what’s missing is the actual promise of the old packaging. Many times I bought albums because the cover lured me in, not because I knew anything about the music. Often these records became favorites—an album of modern gamelan music with a short man wearing a huge mask on the cover, Amarcord Nino Rota, and Gal Costa’s “India†for example. Because I purchased them “sound unheardâ€â€”as opposed to hearing snippets online—I was invested in listening carefully to every note in order to decide whether I liked the music.

The ability to hear snippets of music online is both good and bad—good, because you can get an idea of the music; bad, because you don’t get the whole idea. You make judgments quickly, and often unfairly. Given this mode of quick decisions, perhaps what we ultimately listen to is actually much more limited than before, despite the actual availability of a greater range of music.

The ability to hear snippets of music online is both good and bad—good, because you can get an idea of the music; bad, because you don’t get the whole idea. You make judgments quickly, and often unfairly. Given this mode of quick decisions, perhaps what we ultimately listen to is actually much more limited than before, despite the actual availability of a greater range of music.

So maybe there’s a design challenge here—how can we add a visual element to an audio file that that lets our imagination go to work?

Tags: audio files, CDs, Design, LPs, Packaging, record jackets, Recorded Music

Posted in Uncategorized | 8 Comments »